The article has initially been published on Investigate Europe and is part of the joint IE-RU investigation on Minor Migrants.

Almost four years after the European Union signed a deal on refugees with Turkey, more than 40,000 children, women and men are trapped in camps on five Greek islands. Signed in March 2016, the EU-Turkey statement sought to end the largest migration into Europe since World War II, triggered by the war in Syria. The deal stated that people arriving irregularly – for example by boat – would be returned to Turkey if they were ‘not in need of international protection.’ EU Member States agreed to instead take one Syrian refugee from Turkey for every Syrian returned from the islands.

The influx of refugees and migrants never stopped completely. It only disappeared from the news for a few years – until last summer. That is when traffic across the Aegean increased, still mostly by people from countries at war: Afghanistan and Syria. It is extremely dangerous for anyone to set off across the Mediterranean on a fragile vessel in the winter. Still, almost 10,000 people reached Greece in November 2019, mostly by sea. Every third arrival was a child. This is still a fraction of those who came in the autumn of 2015, but it is enough to overstretch a reception system already on its knees.

The big difference between 2016 and 2020 is that the journey now stops in Greece, either on the islands or in camps on the mainland that the authorities have had to set up to relieve the islands. Since 2016, more than 245,000 young and old who have fled war, persecution, financial hopelessness or combinations of these, have applied for asylum in Greece.

The asylum seekers are crammed together on the islands of Lesbos, Samos, Chios, Leros and Kos, as well as on the Greek mainland. They are being held in camps that relief experts say could have been made habitable in a short time. Money has been allocated from the EU and from Norway, but after almost four years conditions do not survive a closer look.

The situation has worsened with each person that has been picked up by the sea and taken by bus to the camps. Every day, new people are led there. The Moria camp in Lesbos was set up for 3,500 people. Now it has more than 20,000 inhabitants, almost six times its capacity. There is similar dire hardship and distress in the camps on the other islands. Tension erupted in early February 2020, when asylum seekers went to town to protest their conditions in Lesbos. Riot police responded with tear gas.

Outsourced to Greece

Gerald Knaus heads a small Berlin think tank called the European Stability Initiative. The Austrian has often been called the architect of the EU-Turkey deal, an agreement made by desperate governments, with Germany’s Angela Merkel at the forefront.

If the EU-Turkey agreement fails — something that could happen soon in Greece — the result will be a disaster, Gerald Knaus told Investigate Europe in December 2019, explaining that this winter is the worst since 2016.

After the agreement was signed, arrival figures fell like a stone, although the war in Syria continued at full force and continued to drive people from their homes. Almost four years after the EU-Turkey statement (see fact box), Northern European countries like Norway, Denmark, Sweden, Finland, the Netherlands and Germany have the lowest numbers of asylum seekers in years.

In Norway, 200 shelters have been shut down since 2015, when 31,500 people applied for asylum. At the peak, the Directorate of Immigration could offer 40,000 beds. Today, there are 20 receptions centres, with a total of 2,535 residents.

Some of the villages that used to have shelters and jobs connected to them have protested at the closures. In Grong, people held a demonstration lit by burning torches. But there are not enough asylum seekers to keep the centres open. Last year in Norway, 2,304 people applied for asylum. The Directorate of Immigration is planning for a similarly manageable number in 2020: 3,000 people. But that requires several things, notes the Directorate. First and foremost, the EU-Turkey agreement must hold.

Gerald Knaus warns against taking this prospect lightly. A unofficial memo from the German Ministry of the Interior, seen by Investigate Europe, reveals that the German government is thinking along the same lines. The EU’s most powerful country intends to shake other Member States from the delusion that the issue has been handled. As we shall see, Germany is preparing to require all countries to accept asylum seekers based on specific allocation criteria.

Lining up to survive

The sound of Moria is raw, sore coughing from small children.

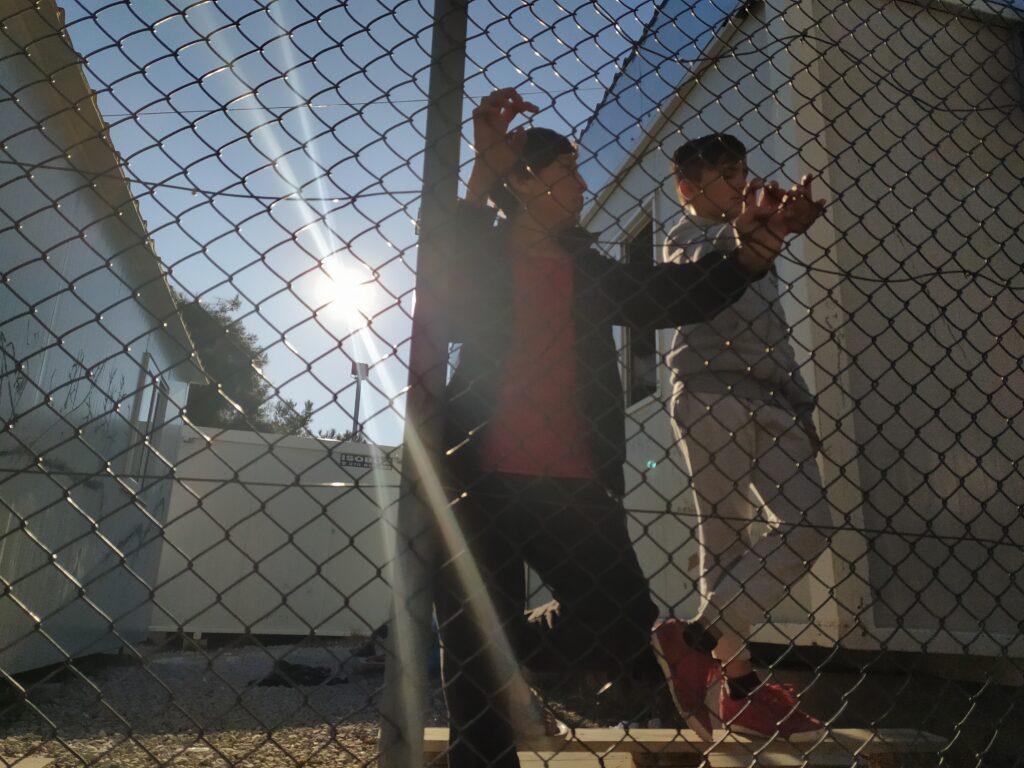

The sight of Moria is high fences with barbed wire rollers on top. Inside the fence are closely stacked iso-box containers, while outside the fence, tents are pitched as far as the eye can see. It is dark between the tents at night, since electricity is lacking. As soon as it rains, the ground turns to mud. Clotheslines are strung between tents. Toddler-sized pants and sweaters hang from many of them.

People in Moria are kept busy surviving. They stand in line. There are queues in front of the toilets. There are queues to shower, often in cold water. Just before Christmas 2019, Moria’s internal statistics showed that there were 57 people per toilet, 40 people per tap and 82 people per shower. That was on paper. In reality, many toilets and showers were out of order. People must position themselves in the lines before it gets urgent.

Everybody quickly learns one Greek word: perímene, wait.

Ahmad Reshad Mahdiyar says he lines up three times daily to get food rations for himself, his wife and their two daughters of three and two years.

“I stand two hours in the morning, two hours in the middle of the day and two hours in the evening,” says Mahdiyar. He is a musician from Kabul, Afghanistan, and tries to take care of his small family. It is not easy in the ‘jungle,’ as the area outside the official camp is called. His little girls cough and have a fever. “We’ve got cough syrup, but it doesn’t help,” he says.

Stress system

Almost half of those coming across the sea now begin their journey in Afghanistan. Decades of war have scarred an entire people and shattered their hopes for the future. The situation of the Kabul musician and his family is typical for the jungle: they are pressed together in one half of a tent. Behind the non-soundproof wall of cloth lives another equally overcrowded family that they did not know until a few months ago, with their own feverish children.

No one in Moria knows how long they have to endure, or what to expect if they are transported out of here.

“The stress level is high. There are delays in all areas,” says Swedish aid worker Patric Mansour. “All the frustration is placed on the individual, who lives in uncertainty. There is stress in the food line, in the queue to the toilet, in the queue to meet EASO, the European Asylum Support Office. You go to a meeting you may have been waiting for a whole month, just to be told to come back in three months. There is violence and crime. People fight for little things because of stress.”

We can watch his musical performances on YouTube, Mahdiyar says. With one little girl on his arm, he borrows a mobile and finds a pop video called Dukhtar Afghan – Afghan daughter. It shows another version of the man in front of us. This one drums with his fingers on the steering wheel of a slick Toyota, dances in snow-clad hills, and performs on stage, wearing sunglasses. Glimpses of a young woman, also in sunglasses, come and go.

Mahdiyar has kept his long guitar nails; he teaches music in a day school that Afghan refugees have established in the camp, thanks to money provided by a volunteer community in Norway. But he no longer wears sunglasses. Dark shadows under his eyes speak a language of their own. The woman with the sunglasses has also vanished. Not many women in Moria have the energy to consider how they look. They are scared, for themselves, for their children, for everything. The showers and toilets they must use can be several hundred meters away. Anything can happen on the way there. Many do not dare go after dark.

Death traps

The iso-box containers inside the barbed wire fences can be engulfed in flames in no time. In September 2019, perhaps after a short circuit, a fire started so quickly that a young woman – an Afghan mother of a toddler – was unable to escape. Seventeen others were injured, and the residents of seven containers lost their homes and meagre possessions.

Parents cannot guarantee their children’s safety. Nor can they secure access to doctors or medication. In November, a nine-month-old baby from the Democratic Republic of the Congo died in the camp from severe dehydration.

More than 1,200 children and teenagers in the camp do not have parents. In August, a 15-year-old boy from Afghanistan died after being stabbed by another Afghan 15-year-old. It happened inside Moria’s so-called ‘safe zone,’ a closed off area where unaccompanied children are supposed to be protected from the dangers of the camp.

“The safe zone is a good idea,” says Katrin Glatz Brubakk, psychology specialist at the Norwegian University of Science and Technology. For long periods of time in recent years, Glatz Brubakk has worked at the clinic that Doctors Without Borders runs a stone’s throw from the main gate to the Moria camp. “But the staff has orders to leave if a conflict arises. They lock the gate as they leave. This means that there was no escape for the boy who was killed. The effect is that when it really matters, young people are locked up without help and support.”

The structure is the problem

“People are stuck here,” says Patric Mansour. The Swedish aid worker worked in the Moria camp for four years before recently leaving. Mansour had been financed by Norcap, an emergency response force in the Norwegian Refugee Council that gets its money from Norway, Sweden and the EU.

Doctors Without Borders and several other relief organizations refuse to work inside the gates of the camp. They withdrew days after the EU-Turkey agreement came into force, protesting a system they perceived as unfair and inhumane.

Mansour’s mission, however, has been inside the fence. He worked closely with the Greek camp management. He has tried to make sure the camp had electricity and water. He has been trying to wiggle loose money that has been allocated but not paid. But he slowly began to lose hope.

Before arriving in Greece, Mansour worked for many years in refugee camps in Palestine, Lebanon, Jordan, Syria, Pakistan, Indonesia, Sierra Leone, Tunisia and Yemen. “You would think that refugees coming to a European country would face proper conditions with infrastructure, water and health services. But here it has been more difficult than anywhere else,” Mansour told Investigate Europe in November 2019.

Emergency aid is an industry with professionals who know how to set up functioning camps for hundreds of thousands of refugees. “But here, despite funding and available expertise, it is very difficult to get things done. The politics are complex, both locally and nationally. And we do not have the same mandate to intervene as we have in many other countries,” Mansour said. He saw no serious improvement on the horizon: “The problem here is not the people. The structure is the problem. The situation is created by a lack of political will to improve the situation. Instead, the police have to deal with all the bad things that happen because of this.”

Hold other states to account?

Conditions in the camps in Greece shock everyone who sees them up close. “This no longer has anything to do with reception of asylum seekers. This has become a struggle for survival,” said Dunja Mijatovic, the Council of Europe’s human rights commissioner, after visiting some of them in October last year.

Psychologist Katrin Glatz Brubakk is equally upset: “No politicians can honestly say that they do not know what is going on. You must be blind, deaf and dumb to not be aware of this. If it is allowed to continue, it is due to a complete unwillingness to take in the suffering we are actively causing people. At least we can offer people conditions that do not hurt them.”

Support for the Greek camps from other countries is based on a rather cynical mindset, according to Mads Andenæs, professor at the University of Oslo and former head of the UN working group on arbitrary imprisonment: The money helps the camps continue to effectively contain people.

Governments that contribute financially to the operation of the camps, however, must assume legal and moral responsibility, says Andenæs. “It does not suffice to claim that conditions would have been worse without the assistance. That may be, but it may also be that the camps would not have existed without this help.”

Right now there is no political will to hold anyone responsible for the serious human rights violations that are taking place in the camps. But that may change, Andenæs believes. “In a few years, actions that are explained as political necessities today may also in a political context appear as arbitrary detention and as gross violations of law and humanity.”

Greece and Europe are breaking every law of dignity and security, explains Gerald Knaus, from his office in Berlin. “Conditions in the camps are as if they were in backwards regions of Pakistan. They are awful, un-European and illegal. I don’t think any European will stand behind them,” says the man who put all his stamina and prestige into making this model work.

Theory met reality

The EU-Turkey agreement was meant to give the Greek government, along with other European governments, some respite in order to put in place more sustainable asylum policy schemes. The Moria camp and other so-called ‘hotspots’ on Greek islands were meant to only be transit places for registration and possible return to Turkey by people whose applications were judged to be baseless.

Everyone else was to be transferred elsewhere in Europe, but it was unclear exactly where to. Four Eastern European EU countries — Poland, Slovakia, the Czech Republic and Hungary — refused to accept any relocation system. Initially, however, EU heads of government promised that 160,000 asylum seekers in hotspots in Greece and Italy would be distributed across Europe to relieve the two countries on the Schengen border.

Gerald Knaus believes his model worked in theory, and should have worked in practice. As it turned out, four brutal factors disrupted the theory:

1. Europe turned its back

The first problem is the mood of the European public, which consists of over half a billion people. Since 2015, when 1.2 million refugees and migrants came walking along roads and railroad tracks from Greece, the notion of immigration as an existential threat to the continent has taken hold in many European minds.

The promise from the summer of 2015 to distribute 160,000 asylum seekers from Greece and Italy among other countries, was not heeded. Eighteen months later, other European countries had taken a third of the people they had promised to receive from Greece.

In 2018, five of the EU’s 28 member states received as much as 75 percent of the asylum seekers to the union. Some countries carry a burden 300 times heavier than others, according to the unofficial memo from the German Ministry of the Interior.

When the Greek government in September last year appealed to other countries to divide 2,500 of the country’s then 4,500 single minors between them, there was practically zero interest across the continent.

The Greek prime minister, Kyriakos Mitsotakis, did not even try to hide his frustration when he explained the situation to the Athens parliament in November: “We attempted to reach agreement with all EU states, saying ‘for God’s sake, we are talking about 3,000 children… can they not be shared out among 27 countries so that Europe can show solidarity?”

2. Greek bureaucracy and resistance

The second obstacle to the system Knaus outlined is Greek bureaucracy. Before 2013, the country had no specialised asylum authority. Even with considerable help, the task of being Europe’s gatekeeper has been too big for the new system. The young Greek bureaucracy has not been able to process the enormous caseload both fairly and effectively.

In the first 33 months of the EU-Turkey agreement, 84,000 asylum seekers came to Greece from Turkey, most of them from war-torn countries. As 2019 ended, only 2,000 people have been sent the opposite way, most of them from Pakistan.

As applications pile up, the endurance of Greek islanders has also reached breaking point. Local people have never been asked whether their small communities can or will assume a permanent role as Schengen border hosts on behalf of over 500 million Europeans. Lesbos now has 86,000 inhabitants and over 20,000 refugees.

In 2015 and 2016, people on the islands mobilised massively to rescue and assist the seemingly endless number of men, women and children who were coming to their rocky coasts. But back then, the new arrivals were headed for the mainland. Today they are not allowed to leave.

Many Greeks don’t believe their own government is able to get out of the role that Europe has assigned them. Protests have become loud and angry, both on the islands and the mainland. Some right-wing groups have threatened migrants and their helpers.

Before Christmas 2019, the Greek government announced that anyone coming to Greece would be detained while their applications were processed. But, in January 2020, when elected officials from Athens came to the Chios Municipal Council in the eastern Aegean to discuss plans for a new closed refugee centre, they were booed and harrassed by a crowd that subsequently smashed the front door of the city hall. After a marathon debate, politicians rejected the plan for a closed centre.

The government has now proposed to install a floating barrier in the ocean off the coast of Lesbos to prevent small boats from reaching the island shores from Turkey. For now, the Ministry of defence has announced a 500.000 € tender for a 2,7 km long test barrier in the Western Aegean, to be followed up by a longer barrier on the refugee route if successful. A plan which has been slammed by human rights groups who say it will hamper life-saving efforts to rescue people making the dangerous sea crossing.

3. An unpredictable president

The third disturbance is on the other side of the Aegean Sea, in Turkey. President Recep Tayyip Erdogan has many conflicts with the EU. He often threatens to “open the gates” to Europe for millions of refugees if he does not get it his way.

No country in the world hosts as many displaced people as Turkey. The state has made room for over 3.6 million Syrians fleeing war in the neighbouring country. On top of that, 360,000 refugees from other countries, almost half from Afghanistan, have been registered by the UN high commissioner for refugees.

The EU pledged EUR 6 billion to Turkey until 2019 to deal with refugees who would otherwise be trying to reach Greece. In December last year, the European Commission announced that contracts have been signed for just over four billion Euros and that just under three billion of the money has been distributed.

“The public here is told that the money is coming in, but that it is insufficient and too slow, and that Turkey is sacrificing much more than Europe,” says Nigar Göksel, head of the conflict-prevention organisation Crisis Group in Istanbul.

At the same time, Turks are living through an economic crisis, with unemployment and high inflation. It is especially hurting many in the unskilled, informal sector, where not just Syrians, but undocumented and unprotected Afghans and Pakistanis compete with Turkish people for the same jobs.

“Every third Turkish citizen works in the black economy. There, employers have gained a strong advantage: They can always tell people that they have an Afghan who will work for lower wages. The Turkish citizens who are being replaced in the labour market are angry, and this anger is also directed at Europe,” Göksel explains.

4. New refugees from Syria

Erdogan took controversial military action last autumn: He ordered the Turkish army to cross into Syria’s border to displace Syrian-Kurdish militia and create what Erdogan calls a ‘safe zone’ in the war-torn country. There, he plans to send up to three million Syrian refugees. He has proposed building ten cities with hospitals, schools and industrial sites for one million people — and using foreign money to fund it all — around $26 billion.

“Hello EU, use common sense. I’ll say it again: If you try to call our operation an invasion, our job is simple: Then we open the borders and send 3.6 million refugees in their direction,” Erdogan said. The EU and Nato have all diligently avoided the word ‘invasion’ in their guarded criticism of what happened. But the EU has refused to fund aid for refugees in the ‘safe zone.’

Another unpredictable element is the war in Syria, which continues to rage in parts of the country that the Syrian regime has not yet recovered. In Idlib province, which borders Turkey, hundreds of thousands of civilians have fled the bombing and fighting. By Christmas 2019, 120,000 refugees had set a course for Turkey, according to a relief organization.

The Turkish/Syrian border remains closed, with Erdogan warning that Turkey cannot handle a new wave of refugees by itself. This pressure will be felt by all European countries, especially Greece, the president said.

After a visit to Ankara in January 2020, German chancellor Angela Merkel has pledged to help Turkey build brick homes for refugees in Idlib. She also assured Erdogan that the EU will supply the EU-Turkey deal with more money.

Greek plan a ‘bluff’

Back in the offices of the European Stability Initiative, Gerald Knaus does not believe the agreement with Turkey will collapse. He sees it as a great success: “It has allowed 99.6 percent of Syrian refugees in Turkey to remain in Turkey, since the EU is actively paying for their integration there.”

In Greece, however, he thinks conditions are on the brink of collapse. Knaus believes that the Refugee Convention — the common document that has guaranteed refugees protection since 1951 — is at stake. He sees the Greek government’s plan to detain everyone who comes as a sign of desperation. “Greece processed 36,000 cases in the first instance in 2018. Now, there are 40,000 people on the islands. Should they detain 40,000 people in one year? It would have been illegal, would never work and is obviously a fantasy and a bluff. Nor would it scare more people from coming. If today’s conditions do not work as a deterrent, then I do not think the idea of detention will scare anyone,” Knaus told Investigate Europe.

So why did other European governments let this happen? “There was always a humanitarian crisis on the islands, but not in all of Greece. A certain complacency developed,” Knaus believes. “It was a type of deterrence that seemed to work. Thus, no crisis summits were organized in the EU, and no one seriously discussed how to resolve the situation.”

German plan: Automatic distribution

No discussions – until now.

German authorities want to prevent the system from collapsing. They demand that other countries stop acting as if immigration to Europe was just a Greek matter, or “treating the EU as if it were a smorgasbord,” as an official stated in a press briefing in Berlin a few years ago.

Europe must put in place a common asylum system that is solid, which does not violate human rights or lead to overcrowded detention camps in some vulnerable countries – and one that works, above all, according to the unofficial memo from the German Ministry of the Interior that Investigate Europe has seen. The four-page note is entitled Food For Thought and was distributed to other governments before Christmas 2019.

The German government wants all countries to receive asylum seekers according to a distribution key that takes into account their population and economic level. While German governments have been saying this for years, this time they are designing a system that also aims to encompass Central and Eastern Europe.

This is no easy task. The governments of Poland, Hungary, Slovakia and the Czech Republic in particular are fundamentally against receiving asylum seekers from countries outside Europe. They insist it is a matter for each nation state to decide. Germany’s proposal implies the opposite – national governments must give up authority and accept quotas.

The novelty of the German plan is that asylum seekers should remain at the same external border ‘hotspots’ where they are currently kept, ‘for a few weeks’, until they are registered and their applications roughly processed. Germany also does not rule out locking asylum seekers up. ‘If necessary,’ it may be appropriate to ‘restrict freedom of movement,’ the memo states.

Germany wants to create a new EU body, the EU Agency for Asylum, a development of the existing European Asylum Support Office. This new agency will gradually take over the job that national authorities do today. Everyone who arrives to seek asylum will be registered in the Eurodac fingerprint base. Only those who get through the first assessment will be able to move further into Europe with their application. But not to anywhere they like. Everyone will be assigned one country. This will end the opportunity to apply in several countries. The principle must be ‘once responsible, always responsible,’ according to the German authorities.

Those who are rejected in this first process on the border will be deported from Schengen – but it is not clear where they will be sent. According to the German memorandum, Frontex, the European border police, will contribute to this.

Emergency on the border

The European Commission is working to reform European asylum policy. The Commission’s new president is a German. In the second half of this year, Ursula von der Leyen will get some extra help: Germany takes over the rotating presidency of the EU Council.

Meanwhile, 40,000 children and adults are shivering around the clock in tents and containers on Greek islands. Aid workers in Lesbos see the miserable conditions as Europe’s attempt to scare people from coming. It does not work, states Marco Sandrone, a field coordinator for the Doctors Without Borders children’s clinic outside Moria’s barbed wire fences: “It is quite clear to us that this deterrence policy has failed completely.”

Having worked in refugee camps around the world, Sandrone knows what a disaster looks like. It is a source of shame for him that this disaster is taking place in his own backyard. “Almost everyone I meet from the camp tells stories of incredible conditions they have left, mostly in war zones, to ensure their children a better future,” he says. “They have ended up in a place that for some of them is even worse than what they left.”

Psychologist Katrin Glatz Brubakk continues to return to the small Doctors Without Borders clinic to treat people in dire need. People can tolerate bad conditions for a week, but not for years, she explains. For Brubakk, an urgent priority is the evacuation of thousands of families with children, and the thousands of unaccompanied minors, who should be distributed across Europe. “It could,” she says, “be resolved at a breakfast meeting tomorrow.”

HOTSPOTS

Part of the EU’s plan to gain control over migration to Europe on the Schengen border – before asylum seekers travel further into Europe. Adopted in the summer of 2015 with five camps in the Greek islands (Lesbos, Kos, Samos, Chios, Leros) and initially two in Italy (Lampedusa and Taranto). The European Agenda on Migration promised to help particularly burdened countries on the border to quickly identify, register and take fingerprints of asylum seekers. The EU Asylum Support Office (EASO) would help process asylum applications. The police force Frontex would help coordinate the returns of those who were rejected. Europol police cooperation would help break up smuggling networks.

EU-TURKEY DECLARATION

Valid since March 20, 2016. The EU promised to pay Turkey six billion euros by 2019 to take care of Syrian refugees in Turkey. Those who still arrived in Greece would have their asylum applications processed there, and those who were rejected would be quickly sent back to Turkey. For each Syrian person returned, other European countries would receive in an orderly way one other Syrian that had not attempted to cross the Aegean in a rubber boat – up to 72,000 people. By the end of 2019, 367 Syrians had been returned from Greece to Turkey since 2016. Meanwhile, European countries have resettled a total of around 20,000 Syrians from Turkey. The EU-Turkey deal does not affect refugees and migrants from other countries.

Turkey has 3.6 million refugees from neighbouring Syria and nearly 400,000 from other countries.

Source: EU Council