Secrets of the Council

The Council of the European Union: 27 Governments. 150 committees. Unnamed diplomats. Secret negotiations. Thousands of paragraphs written into the laws that govern our lives. That is why Investigate Europe, in cooperation in Greece with Reporters United, will be following the Council’s proceedings closely, reporting on which governments are blocking or watering down legislative proposals, and with whom they are in league.

The Greek version of the story was published in three articles by Efimerida ton Syntakton and Reporters United. You can read the first, second and third publication and learn more about Investigate Europe’s Secrets of the Council investigation here.

Editing by Georgia Nakou and Sindhuri Nandhakamur

The proposed Directive on gender balance on boards (also known as the Women on Boards Directive) was first proposed by the European Commission in November 2012. The proposal would require member states to pass laws requiring all Boards of Directors to reach a quota of 40% female non-executive directors by 2018 in the public sector, and by 2020 in the private sector. In November 2013, the proposal was adopted by the European Parliament, which added a requirement for stiffer penalties against companies that failed to meet the quota, including a ban on receiving public funding.

Despite the European Parliament’s push for progress, in the intervening seven years, the proposal has failed to get the backing of enough member states in the Council of the EU, where a qualified majority vote is required to approve it. In the Council, which shares legislative powers with the European Parliament, representatives of member state governments negotiate and vote according to national positions. A qualified majority requires both 55% of member state votes and that those votes represent 65% of the total EU population (Council voting outcomes can be tallied using this online voting calculator).

Some of the opposing member states had, in the intervening period, published reasoned opinions from their national parliaments opposing the directive on the grounds that board quotas should be legislated at the national, rather than EU level. These include Denmark, the Netherlands, Poland and Sweden.

Until recently, Greece had not published or justified its position.

Member states are not obliged to report their positions in the Council or publish their reasoning, meaning that decisions taken in the Council chamber often lack transparency and accountability to citizens at home. Transparency on national positions, for example, “would allow feminist groups in those Member States to organise a targeted campaign on it.”, according to Grace O’Sullivan, a Green MEP representing Ireland. “This might be particularly effective in the run-up to national elections.”

During the second semester of 2020, the rotating presidency of the Council was held by Germany — one of the major opponents of the initiative. This naturally made progress on the draft directive unlikely. On the other hand, Brexit changed the voting calculus significantly by removing another known opponent of the directive from the tally.

Diplomatic sources with good knowledge of Council matters (who requested anonymity) told Investigate Europe that “just two smaller countries” changing position in favour of the proposal would be enough to tip the balance. One of the countries named was Greece.

The Greek position — government claims vs. reality

Despite proclaiming himself in favour of reforms, Greek Prime Minister Kyriakos Mitsotakis’ commitment to gender equality has been questioned. At the time of writing, Greece has only 11 women in a cabinet of 58, only two of whom hold ministerial posts. When a BBC interviewer asked Mitsotakis why there were so few women in his cabinet, the PM responded that there were not many women “who were interested in stepping into politics these days”.

Low numbers of women in senior government positions directly contributed to Greece plummeting 14 places in the WEF Global Gender Gap report in 2021. Greece also lags behind most European countries in terms of women in senior decision-making positions. In 2020, only 13% of board positions in Greece were held by women.

Investigate Europe and its Greek research partner Reporters United contacted the PM’s office twice, once in October and once in November 2020, asking the government to state its position on the Women on Boards Directive. Both times, the requests were met with silence.

In February 2021, IE’s Greek media partner Efimerida ton Syntakton published the findings about and how the government was blocking the directive. The article prompted a response from Deputy Labour Minister Maria Syrengela, who is responsible for demographic and family policy.

In her response, the minister claimed that Greece had adopted a position in favour of the proposed directive and continued to support that position. She also disputed the charge that Greece was “blocking” the initiative on the grounds that one small state could not prevent the adoption of the directive.

None of these claims were true, as further research showed.

Firstly, the European Parliament just recently published an update on the directive in its “Legislative Train” schedule, where it reports on the progress of EU legislation. The report states that still in May 2020, Commission Vice-President Věra Jourová told the European Parliament’s JURI committee that Germany, along with eight smaller member states, including Greece, continued to oppose the gender balance directive.

Secondly, Jourová also stated that the balance in the Council was close, and could be swung if Germany supported the proposal. Opposition to the proposal has shifted significantly since the other vehement opponent of the directive, the UK, left the EU. Two separate sources confirmed that two small countries (one of which is Greece) could also tip the vote in favour of the proposal, by achieving a qualified majority in the Council without agreement from Germany – meaning that Greece could in fact play a pivotal role.

The minister also claimed in her response that since 2017, “the directive proposal has not been discussed in the Council”. This is contradicted by several sources. Firstly, a document produced by the Austrian Permanent Representation to the EU refers to an informal meeting by video conference held on October 13, 2020, between the member state’s ministers on the Employment, Social Policy, Health and Consumer Affairs Council (EPSCO), which addressed this particular issue. According to the Austrian document, there was extensive discussion of the proposed directive, and it is reported that, “certain ministers (Slovenia, Portugal, Finland, Belgium and Luxembourg) demanded that deliberations on the proposal proceed immediately. — But Greek ministers were not among them.

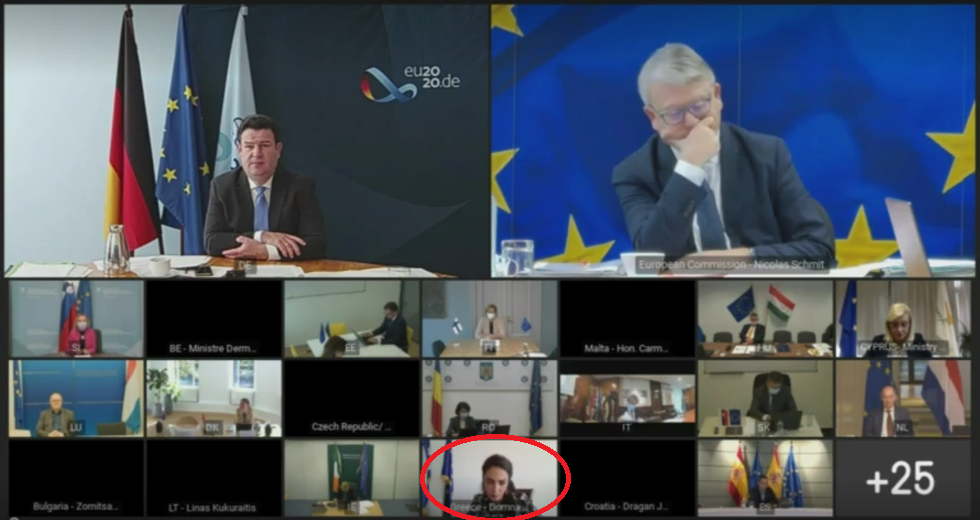

The Council agenda for the video conference states that Greece was represented by Deputy Labour Minister Maria Syrengela, who was then General Secretary for Family Policy and Gender Equality, and the then Deputy Minister for Labour and Social Affairs, Domna Michaïlidou.

Michaïlidou can in fact be seen in an video of the meeting published on the Council’s website.

Finally, the response from the Labour Ministry to the Efimerida ton Syntakton story claimed that, “[t]he Mitsotakis government, prior to any of the countries mentioned in the article, proceeded to pass law 4706/2020, which introduces [gender] quotas for Boards of Directors”.

This is another grossly misleading claim. According to the European Commission’s annual report on Gender Equality in the EU, however, several European countries had in fact introduced legally enforced targets for board quotas before Greece. These include Norway, Belgium, France, Italy, Sweden, and the biggest remaining opponent of the proposed directive, Germany.

In fact, the Greek legislation is much weaker than the proposed EU directive, requiring only 25% female directors, rather than the draft directive’s 40%. It is also weaker than the targets set by any other European country.

- Norway: 40% (2004 → 2008)

- Portugal: 33% (2007 → 2020)

- Iceland: 40% (2010 → 2013)

- Belgium: 33% (2011 → 2017-2019)

- France: 40% (2011 → 2017)

- Italy: 40% (2011 → 2015)

- Holland: 30% (2011 → 2016)

- Germany: 30% (2015 → 2016)

- Spain: 40% (2017)

- Austria: 30% (2017 → 2018)

- Greece: 25% (2020)

(In brackets, the date the legislation came into force, and the end of the transition period)

Not a political priority

It may seem unfair to single out the current New Democracy government for criticism, given that they have been in power for less than two of the seven years that the directive has been stuck in the legislative pipeline. Opposition to the directive seems to stem from a larger attitude towards gender balance — one held by many political parties.

We also approached other Greek parliamentary parties for their position on the proposed Directive.

Yiannis Bournous, an MEP for SYRIZA, the party leading the governing coalition in Greece between 2015-2019, told Investigate Europe that, “for reasons of justice and good governance, we need more women in senior positions of responsibility”, adding that “there is also a need for policies to address unequal pay and protect women’s rights in the workplace”.

KINAL (Movement for Change), which has had several turns in government alone or in coalition in its previous guise as PASOK, did not respond to our request for comment.

Among Greece’s smaller parties, Communist Party KKE was more dismissive of the initiative. “Women’s participation on company boards is presented by the EU, member state governments and their delegations as a supposed measure against discrimination. In reality, participation in the management of capitalist businesses is being used to hide the class-based character of female inequality”.

The leader of hard right party Greek Solution, Kyriakos Velopoulos, said his party “approves of the strategy of board equality, and hopes to see more than 50% participation”, before expressing reservations based on the potential for “unfair treatment of those candidates who do not meet the gender requirement”.

“Take a look at the Greek Parliament῾, says Secretary of DiEM25 party, Yanis Varoufakis. “A sea of suits punctuated by the odd woman. With the exception of DiEM25, whose female MPs outnumber males, the rest of the chamber is filled with testosterone. As for the government, it features a mere two women ministers. Is it any wonder that our government is blocking the EU’s directive on gender balance in companies? Given the political system’s resistance to quotas in public life, it would be surprising if it supported them in the private sector.”

The parties’ responses suggest that, while there may be no outright opposition to it, the issue of women on boards is unlikely to top Greece’s national agenda under any political configuration. This raises the possibility of an alternative scenario to explain the Greek position, which was held by a series of governments prior to the current one.

Due to the nature of negotiations in the Council, where compromises are sought behind closed doors, issues which are deemed to be of low national priority often end up being used as bargaining chips to secure agreements on entirely unrelated matters or even to trade votes on unrelated legislation — a practice described in political circles as “horse trading”.

Greater transparency around national positions would help to discourage such backroom tactics which also contribute to the democratic deficit.

A small victory

After the publications, things seem to move on the European level. In her latest correspondence with Investigate Europe and Reporters United Deputy Minister Syringela stated the following:

“In an informal teleconference of representatives of the Greek and Portuguese governments which took place a few weeks ago, Greece informed the Portuguese Presidency of its positive position towards the aims of the Directive, and the draft Directive more broadly.”.

Investigate Europe also contacted the Portuguese Presidency to ask about Greece’s cooperation on the directive. We were informed that the Portuguese Presidency is committed to “unblocking” the progress of the directive by seeking “compromise solutions”. The response concluded, “in this context we have worked closely with the Greek delegation, which has shown a positive attitude to this issue and a willingness to work with the Presidency”.

The response suggests that the Greek government has in fact not expressed unreserved support for the directive. However, it does hint that there is more readiness on its part to move constructively in the direction of adoption.

The change of position offers some hope that by shedding light on the government’s actions, investigative journalism can change political outcomes through transparency.

This is not the first time this will have been achieved.

Earlier this year, Investigate Europe caught the Portuguese government non supporting the proposal for public CbCR — Country by Country Reporting, a tax transparency directive aimed at stamping out corporate tax avoidance by requiring multinationals to disclose the income tax paid in each member state. While the Portuguese government had publicly criticized tax evasion and underlined the need for EU legislation to deal with the problem, a leak from a German MEP revealed that Portugal was one of the countries blocking the agreement.

The story, published by Investigate Europe’s Portuguese media partner Diário de Notícias, forced the Lisbon government into an about-turn in support of the directive. More recently, the Portuguese Presidency went one step further, by putting the public CbCR directive back on the agenda in the Council, where they negotiated broad support for the legislation. Hopefully the Greek government will follow the same path.